In a recent hearing decision, IsoLynx, LLC [2022] NZIPOPAT 16, the New Zealand Patent Office (IPONZ) has confirmed that certain computer implemented inventions are patentable subject matter under s 11 of the Patents Act 2013. Importantly, this decision is an excellent example of the various factors that are taken into consideration for determining patentable subject matter under s 11 and highlights the importance of the interworking relationship between a patentable computer implemented invention with real world conditions according to New Zealand patent law.

Background

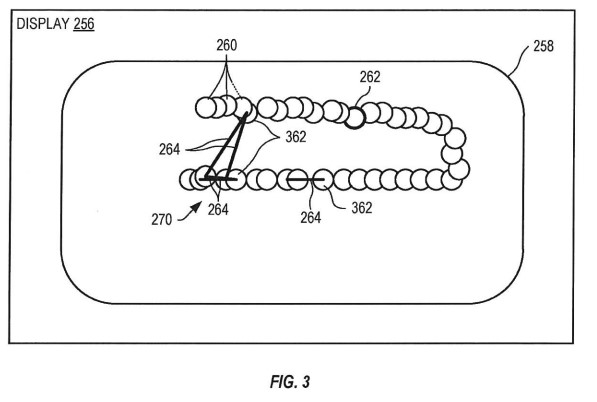

New Zealand patent application 748919 was filed by IsoLynx, LLC. The claims were directed toward various aspects of an optimization tool for displaying errors of a tracking system. In particular, the invention involved use of a tracking tag carried by a person which transmitted a wireless signal to be located by the object tracking system. The invention attempted to detect erroneous calculation of the tracking tag location by providing an optimisation tool to display a graphical representation of the tracking of the tag by plotting vectors between chronologically consecutive calculated locations. As exemplified in Figure 3 reproduced below, a location pair having an incorrectly calculated location is presented as a vector 264 visibly extending between the location pair thereby visually highlighting to the user the location error.

During examination, objections were raised under s 11 where the Examiner asserted that the claims were directed to a computer program as such. Despite multiple responses, the objection under s 11 was maintained by the Examiner.

Legislation

Section 11 of the Patents Act 2013 is outlined below:

11 Computer programs

(1) A computer program is not an invention and not a manner of manufacture for the purposes of this Act.

(2) Subsection (1) prevents anything from being an invention or a manner of manufacture for the purposes of this Act only to the extent that a claim in a patent or an application relates to a computer program as such.

(3) A claim in a patent or an application relates to a computer program as such if the actual contribution made by the alleged invention lies solely in it being a computer program.

Unusually s 11 provides an example of a patentable invention (a better method of washing clothes when using an existing washing machine where the method is implemented through a computer program on a computer chip within the washing machine) and an unpatentable invention (automatically completing legal documents necessary to register an entity). As many would recognise, the “as such” requirement is a reference to Aerotel Ltd v Telco Holdings Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 1371.

Decision

The Hearing Officer agreed with the Examiner’s conclusion that the substance of the claims related to identifying erroneous tracking tag locations by plotting symbols representing the locations and generating a line connecting a pair of consecutive locations such that the line is only visible when at least one of the locations is erroneous.

The Hearing Officer then concluded that the problem the invention addressed was the incorrect display of one or more tracking tag locations on a graphical representation of a tracking area. The substance of the invention provided the advantage of allowing a user to see something they could not easily see before due to the density of the locations plotted on the graphical representation.

The Hearing Officer also noted that in addition to the problem to be solved, the solution and the advantage provided by the invention, other matters which are relevant must also be considered. In particular, the Hearing Officer noted at [43]:

A notable aspect of the invention claimed is that it takes place or is “worked” in the real world. Receivers receive data from a physical tracking tag in a physical tracking area. Locations of the tracking tag are calculated by computer on the basis of the received data. There is a graphical representation involved, but it is not of something abstract. The graphical representation is of the actual tracking area. What is shown, on top of the graphical representation of the tracking area, are symbols that identify, on the displayed tracking area, the real-world real-time locations of a tracking tag. Inherent to the claimed invention is an interaction with the real world.

The Hearing Officer then went on to consider that the actual contribution of the claimed invention over the prior art. The Hearing Officer concluded that the actual contribution was the generation of a line connecting pairs of chronologically consecutive locations on the graphical representation where the line is only visible when at least one of the chronologically consecutive locations is erroneous.

The Hearing Officer also went on to consider the five AT&T signposts (see paragraph 37 of IPONZ’s examination manual concerning computer programs.

In relation to whether the claimed technical effect has a technical effect on a process which is carried on outside the computer, the Hearing Officer concluded that:

The effect of the present invention is to give a visual indication that one or more tracking tag locations shown on a display of a tracking area is/are incorrect. I consider this effect to be outside the computer. The effect is to show that something in the representation of location data – the “display” – is going wrong. It is a signal, a message. Showing an error in a tracking system display is more than just a computer program running. It is a computer program doing “work”.

Whilst the Hearing Officer concluded that the second, third and fourth signposts were not satisfied by the claimed invention, the Hearing Officer found that the fifth signpost (i.e., whether the perceived problem is overcome by the claimed invention as opposed to merely being circumvented) was also satisfied.

The Examiner also went on to consider the nature of the invention, stating at [89]:

The invention starts in the real world. The incoming data – data relating to the position of a tracking tag relative to at least three receivers – is information about the real world that is dynamic, changing moment by moment. The data is processed to yield location information, and this information is plotted in the form of symbols on a “map” of the tracking area around which the receivers are positioned. This is known. What was not known was how to recognise errors in the mapped locations. The actual contribution is to make those errors known to a user by providing a visual indication of where those symbols show locations wrongly.

Furthermore, at [93], the Hearing Officer concluded that a general-purpose computer could not carry out the invention by reasoning:

The data-packet received from the receiver needs dedicated “reading” and processing for a location to be derived from it. The generation of the graphical representation of the tracking area would require dedicated graphics programming, as would the plotting of location symbols and connecting lines for consecutive chronological locations. The tracking computer and optimisation tool are both dedicated devices.

The Hearing Officer finally considered whether the provision of error-information was an identifiable effect outside the computer. At [96] to [99] the Hearing Officer concluded:

The claimed invention provides an indication of the truth-status of content in a representation of dynamic real-world data – not of inventoried data of some kind. In this sense there is a real-world interaction. It is not merely that the data comes from the real world in real time, the invention includes a ground-truthing of the representation of that data. The contribution comes from the real world and is about the real world. In particular: are real-world data accurately represented?

Adding to the display in a way that communicates something about the display itself – where it contains error(s) – is not just changing the display in a cosmetic manner (as in Gemstar, making the information “better” for a user, from a perception and interaction point of view), but a change that does actual “work”. The change says something about the relationship between the display and the real world. It identifies a mismatch between the display and real world. The contribution lies in the interaction or interplay between real world conditions and what the display shows.

Even though this is realised by a computer in a computer display, the contribution is not in a computer program and nothing more. The contribution is not in the software or program. Nor is it in the hardware or the way the computer works. The contribution is to tell the user something useful about a display of real world conditions.

In my view, there is an identifiable effect outside the program. The actual contribution is more than a computer program as such.

Ultimately, the Hearing Officer concluded that the claimed invention was patentable subject matter according to s 11 of the Patents Act 2013.

Take Away

This decision is a welcome clarification on the patentability of computer implemented inventions in New Zealand. This decision highlights that certain computer implemented inventions which operate in the physical real world can be considered patentable subject matter. Applicants looking to patent a computer implemented invention in New Zealand should take note of this decision, particularly when there is some form of interaction with the physical real world.